Avoid Narrow Framing & Instantly Improve Your Decision Making

A technique from behavioral psychology book 'Decisive' by Chip & Dan Heath

Strategies to make better choices in life and work.

Is that a thing? Isn’t decision-making just something we do? Some turn out good; others turn out bad. You live, and you learn?

Not quite.

Decision-making is a skill and one that we can get better at with self-awareness and practice.

I wrote before about how it’s helpful to adopt a choice-minimal lifestyle for simple, everyday decisions. You want to avoid decision fatigue and save your energy for the decisions that matter.

But how about for bigger life decisions? Where to live, what to study, rent or buy, kids or no kids, etcetera. You want to take those seriously and invest the time to think through all of your options.

Few things will change your trajectory in life or business as much as learning to make effective decisions. Good decisions save time, money, and stress. — Farnam Street

The psychology behind decision making

I recently read Decisive by Chip & Dan Heath, a book about “how to overcome our natural biases and irrational thinking to make better decisions about our work, lives, companies and careers.”

The psychology behind how we make decisions is fascinating.

We believe we’re oh so rational and have considered all our options, but research clearly shows that overall, we are quick to jump to conclusions without considering all the information that is available to us.

The Heath brothers describe the “Four Villains of Decision Making” we should be aware of:

- Narrow framing causes you to focus so much on your immediate choices that you miss other options.

- Confirmation bias leads you to seek out information that will confirm what you already believe.

- Short-term emotion blinds you from making the right choice, even if it should be completely obvious.

- Overconfidence makes you believe you know more than you actually do.

Narrow Framing is the villain that has stuck with me the most, long after reading the book, for 2 reasons:

Firstly, I noticed how often I would fall into this cognitive trap — and not just me, but other people around me as well.

Secondly, it’s a blind spot that is easy to fix once you’re aware of it. The tips I’m about to share in this post are highly practical and will make an immediate impact on your thought process.

What is Narrow Framing?

When making decisions, we often fall back to the pro-con list, where you list all the positive things that happen on one side and the negative things on the other trading them off.

It turns out it’s an okay approach for deciding where to go on holidays; not so great for making critical decisions.

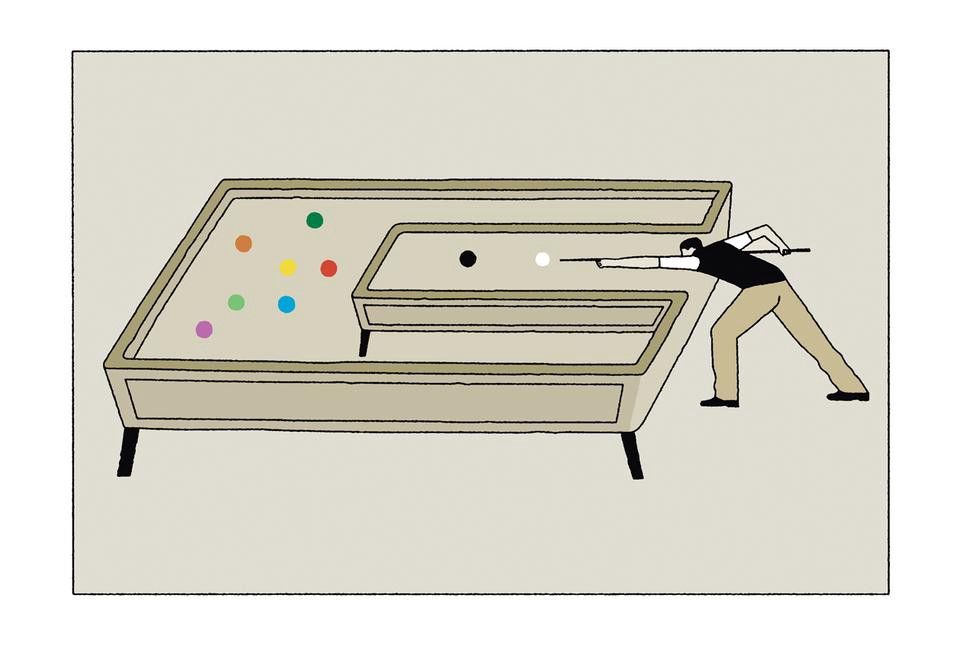

Narrow Framing is when we only see a small sliver of the spectrum of options available to us.

You’ll know you’re stuck in a Narrow Frame the moment you frame your decision as “(whether) or not”; “this or that”; “yes or no”.

It means you’re defining the problem in a way that there are only two possible options to choose from.

- “Should I leave my job or not?”

- ”Should we re-do the bathroom or not?”

- ”Should we buy an apartment this year or not?”

The Heaths suggest that when we spot this type of question, a little alarm bell should go off in our head, reminding us to consider whether we’re stuck in a Narrow Frame and more options are needed.

How to widen your options

The trick to making better decisions is to force yourself to come up with a second or third alternative, which is generally not hard once you discipline yourself.

Doing this will take more time and effort, that’s true, but as I said in the intro — good decisions save time, money and energy down the line. So it’s worth the additional effort now to make sure you have looked at all your options.

Here are 3 ways to do that.

Consider the Opportunity cost

What if you started every big decision by asking these simple questions:

- What am I giving up by making this choice?

- What else could I do with the same time and money?

Every decision has a cost. The first is the actual amount of money, time, or energy you invest. The second cost is the benefit you would have gotten from the next best alternative. This hidden price is called the opportunity cost.

For example, you’re considering buying a brand new car. There’s the cost of the car, and the opportunity cost is that this money could also be used towards renovations in your home.

You want to make the opportunity costs explicit. Write them all down.

If you can’t come up with any other alternatives that seem more important or enticing than your initial options, you should feel more confident that you’re making the right investment.

Talk to people

This is one that I don’t do nearly enough myself. I tend to do much of my thinking in my own head — a fertile breeding ground for Narrow Framing.

One of the most basic ways to generate new options is to find someone else who’s solved a similar problem.

There’s not much more I can add to that, because it’s so simple. Ask them what they have done, how they made the decision, which options they’ve considered and most importantly, how the decision has turned out and whether they would now do anything differently.

The trick is to be creative in who you talk to — don’t talk to your closest friends or relatives. Very often we get locked into a fairly narrow set of people and ideas that we consult.

Just one watch-out here: sometimes we think we’re gathering information when we’re actually fishing for support. Force yourself to be genuinely open to new ideas.

The Vanishing Options Test

This is my favourite.

In the Vanishing Options Test, you have to pretend you can’t choose any of your current options.

What would you do instead? The beauty of this question is that it forces you to think creatively, and consider viable options you would have immediately dismissed otherwise.

Two things can happen here:

You come up with a new option that turns out to be the best one. The Heaths find that about 80% of the time, people come up with something much better than they had initially thought of within three minutes — even if they had been agonising about the decision for weeks before they did the test.

OR

You can’t come up with anything else that’s better, which affirms your previous options and strengthens your confidence that you’re making the right decision.

That’s what happened to my partner and me as we were agonising over where to buy. We ran through all the options we could potentially live if we couldn’t go where we were considering, writing down what that would mean and what we would need to do to make those options work. We ended up sticking with our first option, but it has made me feel so confident in our decision.

The 2+3 Rule

Of course, you don’t want to get overwhelmed by options either.

A good rule of thumb is the 2+3 Rule: before deciding between two options, force yourself to identify at least three more.

If you’re willing to invest some effort in a broader search, you’ll usually find that your options are more plentiful than you initially think.

I’m on a mission to improve my decision making skills and share what I learn. Sign up for my bi-monthly mailing list for more ideas and resources around developing a growth mindset. 🤸♀️