5 Japanese Life Philosophies Worth Knowing

Build your latticework of philosophies for a deeper and simpler life.

Curiosity about Japan is nothing new.

After Japan opened to the West in the 19th century, its impact on the formal and decorative arts became so intense that the phenomenon was anointed as an ‘’ism.’’

Japonism or Japonaiserie has continued to thrive to this day, with influences in technology, anime, martial arts, poetry (haiku), fashion and cuisine.

We also look to Japan for inspiration on lifestyle and philosophy. They’re consistently recognised as some of the longest living and happiest in the world, with 1 Japanese person in every 1,450 aged over 100!

There’s much to learn from this ancient civilisation, so here are 5 Japanese philosophical concepts that can change your approach to life.

But first: why have life philosophies at all?

A latticework of life philosophies

A philosophy of life is any general attitude towards, or philosophical view of, the meaning of life or of the way life should be lived.

The beauty of creating your latticework of life philosophies is that it simplifies situations and decisions. It provides direction and structure.

When there is a conflict or a compromise to be made, it’s easier to know how to feel or how to react, because you have a toolbox of life philosophies to rely on based on your values and priorities.

It’s your way of life, and you’ve done the thinking in advance.

No one defines and packages these lifestyle philosophies better than the Japanese.

Uketamo

The Dewa Sanzan is a little-known mountain range in northern Japan. Since the 8th century, it has been the sacred pilgrimage site for the Yamabushi monks, who partake in yearly rituals seeking rebirth and enlightenment for their mind, body, and soul.

We can sum up the core philosophy of their training in one word: Uketamo.

The literal translation is “I humbly accept with an open heart.”

Uketamo means acceptance to the core.

The Yamabushi understood that the sooner you can accept all the good and bad things life throws at you, the lighter you will feel.

Here’s how it works:

- You didn’t get the job offer you so badly wanted? Uketamo.

- The forecast suddenly changed to downpour rain, and now you must cancel your outdoor event? Uketamo.

- You broke your leg and can’t go on your long-awaited trip? Uketamo.

This idea of radical acceptance can be found across cultures and philosophies, from Nietzsche to the Stoics’ Amor Fati.

Don’t fall into the trap of wishing things were different.

Don’t get stuck on “how things should be”.

Don’t waste time feeling sorry for yourself.

Instead, embrace your reality and deal with it. It doesn’t mean you have to love what’s happening. It just means you quickly understand and accept that you cannot change it, and your best option is to think creatively about how to move forward.

Kintsugi 金継ぎ

Kintsugi is the centuries-old Japanese tradition of repairing broken ceramics with gold.

It means, literally, ‘to join with gold’.

In Zen aesthetics, the broken pieces of an accidentally-smashed pot should be carefully picked up, reassembled and then glued together with lacquer inflected with a luxuriant gold powder.

Every break is unique. Instead of restoring an item like new, the 400-year-old technique highlights the ‘scars’ as a part of the design. There should be no attempt to disguise the damage.

The metaphor for life is clear.

We should embrace and celebrate our flaws and imperfections.

Sometimes, in repairing things that have broken (relationships, careers,…), we can create something more unique, beautiful, and resilient.

Tsundoku 積ん読

This is a term every book lover needs to know.

Tsundoku is the act of buying books and never reading them.

It’s different from ‘bibliomania’ which refers to the desire to simply collect books.

The intent to read is key to the concept of Tsundoku — it’s more about curiosity than it is about collecting.

I love that there is no negative connotation to this. There’s no reason to feel bad about having a huge pile of unread books spread around your home.

The Japanese see it as a tower of potential learning experiences.

The earliest believed mention of the practice of tsun-oku, literally translated as “reading pile” dates back to the 16th century.

It’s fascinating to learn that having a pile of unread books has been around for centuries — and not just a sign of our undistracted, overloaded times.

Non-Japanese side note but interesting nonetheless: Lebanese-American essayist and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb believes that it’s natural to build a collection of unread books over time. He advises embracing them as an “antilibrary”.

Ikigai 生き甲斐

Ikigai is the age-old Japanese ideology that’s long been associated with the nation’s long life expectancy.

A combination of the Japanese words “iki”, which translates to “life” and “gai”, which is used to describe value or worth, ikigai is all about finding joy in life through purpose.

In other words, your ikigai is what gets you up every morning and keeps you going.

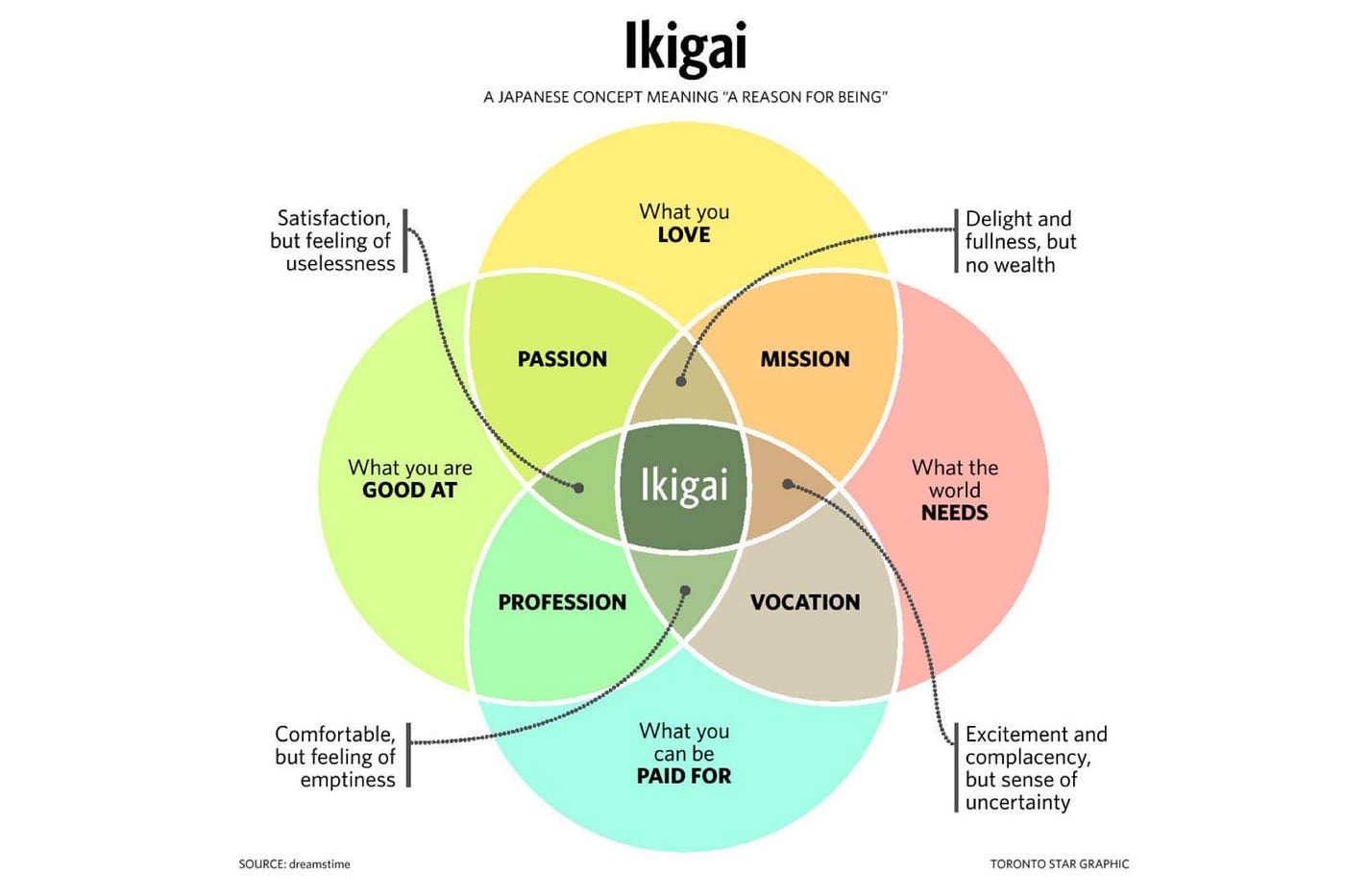

The best way to encapsulate the ideology of ikigai is by looking at the Venn diagram which displays the overlapping four main qualities:

- what you are good at

- what the world needs

- what you can be paid for

- and of course, what you love

Individuals who found their ikigai see the big picture, have a goal in mind and know the why behind what they do.

We all have an Ikigai. It’s only a matter of finding it. The journey to Ikigai might require time, deep self-reflection, and effort, but it is one we can and should all make.

Kaizen 改善

Kaizen means “Change for the better”.

Although technically originally developed by an American businessman, it was used and popularised by the Japanese post-WWII.

Instead of making significant changes overnight, the Japanese adopt a long-term approach that systemically seeks to achieve small, incremental changes in processes in order to improve efficiency and quality.

Kaizen sees improvement in productivity as a gradual and methodical process, and this can be applied to professional as well as personal settings.

There’s no magic bullet or overnight success. Instead of trying to make radical life changes, you should start with small, daily improvements.

Focus on getting 1% better each and every day. Small-scale improvements start compounding on the previous day’s accomplishment.

At first, the changes will seem inconsequential. Gradually, you’ll start to notice improvements.

Over time, there will be profound positive changes.

To recap

We can find inspiration in the beautiful Japanese culture to create a latticework of life philosophies.

- Uketamo: acceptance to the core

- Kintsugi: embrace flaws and imperfections

- Tsundoku: never stop being curious

- Ikigai: find your reason for being

- Kaizen: small, incremental changes for the better